LSU Researchers Envision a More Compassionate, Adaptive Future for Dementia Support Technology Using AI

February 05, 2026

Living with dementia involves constant change, yet the technology designed to help often fails to evolve with the needs of patients and caregivers.

In a new paper, two LSU researchers reimagine technology as quiet, evolving support that uses emerging artificial intelligence technologies to help preserve dignity, ease caregiver burden, and help families navigate dementia more safely and compassionately.

The researchers—Bijoyaa Mohapatra, associate professor in the College of Humanities & Social Sciences, and Reza Ghaiumy Anaraky, assistant professor in the College of Engineering—propose “Assistive Intelligence,” a human-centered approach to AI that adapts as needs change.

“ I hope this work helps move the conversation toward smarter, more compassionate solutions that allow people to age safely at home and support caregivers in sustainable ways. ”

Bijoyaa Mohapatra

Q&A

At its heart, what problem is this research trying to solve for people living with dementia and their families?

Mohapatra: This research is about easing the daily burden that dementia places on people and the families who care for them. Dementia doesn’t just affect memory—it touches communication, independence, emotional well-being, and family life. Too often, care becomes reactive, stepping in only after something has gone wrong.

What motivated this work was seeing how fragmented and exhausting that experience can be for families. Caregivers are constantly on alert, trying to manage safety, routines, and emotional changes with very little support. We felt there had to be a better way—one that anticipates needs, adapts over time, and supports people before crises happen, not just after.

Anaraky: At its heart, this research addresses a mismatch between the lived realities of people with dementia and how technologies are designed. Most systems assume either full independence or complete dependence, ignoring the long middle period where abilities fluctuate and needs evolve. This creates unnecessary stress and added burden for both individuals and their caregivers.

This made it clear that a new way of thinking was needed, because the gap is no longer technical. We can already collect rich data and model change over time; In my prior work, for example, we showed that changes in technology-use patterns are associated with cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting that meaningful signals already exist. The remaining gaps go beyond AI capability alone and relate to how AI is applied in people’s lives.

“ I work closely with older adults to understand their lived experiences and the daily friction they encounter with technology. ... I want to ensure that as technology advances, it serves the aging population rather than marginalizes them. ”

Reza Ghaiumy Anaraky

You introduce the idea of “Assistive Intelligence” in this paper—what does that mean in everyday terms?

Mohapatra: In everyday terms, Assistive Intelligence refers to technology that works quietly in the background, supporting people rather than demanding their attention. It is not about replacing caregivers or overwhelming families with complicated tools. It is about technology that learns routines, notices small changes, and gently steps in when help is needed.

What makes this different from many technologies people know is that it is not static.

Most tools do the same thing every day, no matter how a person’s abilities change. Assistive Intelligence adapts- it might simplify reminders, adjust support, or alert a caregiver as needs evolve. The focus is always on preserving dignity, independence, and peace of mind.

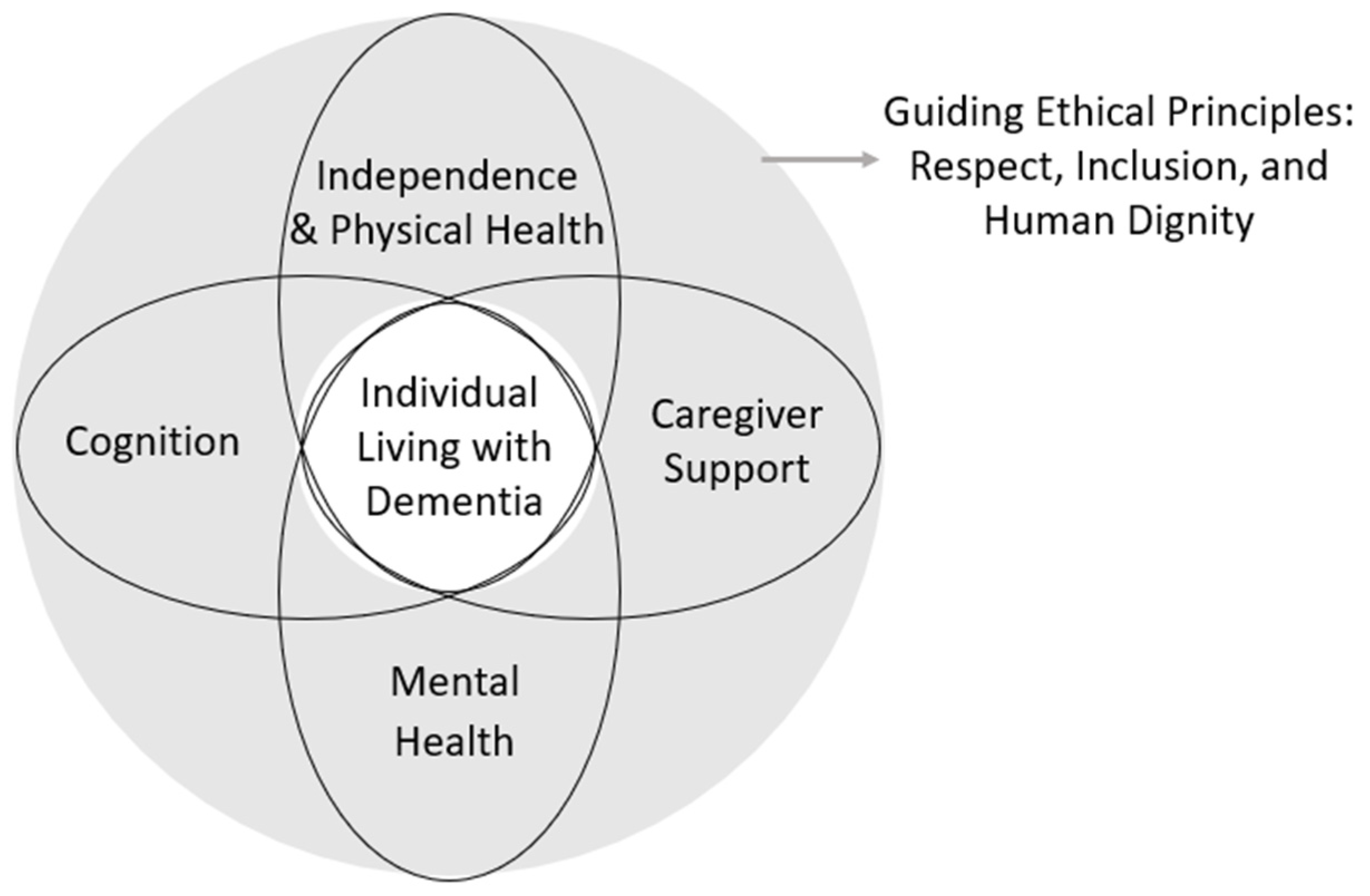

Assistive Intelligence Framework for AI-Powered Dementia Care

Anaraky: Assistive Intelligence refers to smart environments, like a home equipped with sensors, that help people complete tasks on their own rather than taking the task away from them. It adapts to a person’s context, abilities, and preferences, and it changes as those needs change.

For example, instead of a robot that just cooks for you (replacing the human), Assistive Intelligence might be a smart stove that monitors safety and only intervenes if it detects you’ve left the burner on and wandered away (augmenting your safety).

This is different from most AI people are familiar with today, which tends to focus on automation, efficiency, or prediction. Assistive Intelligence is human-centered by design. Its goal is not to optimize systems, but to support people, especially when cognitive, emotional, or situational challenges make everyday tasks harder.

Your research emphasizes supporting people at different stages of dementia. Why is that so important?

Mohapatra: Dementia is a journey, not a single moment in time. Early on, someone may just need

subtle reminders or help staying organized. As the condition progresses, safety, emotional

regulation, and daily functioning become much more important. Eventually, caregivers

need round-the-clock support and reassurance.

When technology doesn’t account for these changes, it often stops being useful or

even becomes stressful. By designing support that evolves alongside the person, we

can offer help that feels appropriate at every stage.

Anaraky: Early on, individuals often want subtle support that preserves independence. Later, safety and caregiver coordination become the priority.

Designing without these stages in mind leads to solutions that either overwhelm people too early or arrive too late. Stage-sensitive support allows technology to grow with the person, offering the right help at the right time without forcing abrupt, stigmatizing transitions.

If these ideas were put into practice, how could they make daily life easier or safer for people with dementia and their caregivers?

Mohapatra: In real life, this approach could mean fewer emergencies and less constant worry.

For example, sensors or wearables could quietly track daily routines and alert caregivers

only when something truly changes, like increased fall risk, nighttime wandering,

or signs of agitation.

That peace of mind can be life-changing. It allows families to focus less on monitoring

and more on spending meaningful time together.

Anaraky: In practice, imagine tools that evolve: a reminder system that starts with gentle prompts but shifts to shared caregiver coordination as needs increase, or decision-support tools that navigate complex interfaces so users don't feel confused.

For caregivers, this means less guesswork and fewer crisis-driven interventions. For people with dementia, it means maintaining autonomy longer and reducing anxiety.

Why is this research especially important right now, as our population continues to age?

Mohapatra: As more people are living longer, more families are facing dementia often without enough support. Healthcare systems and caregivers are stretched thin. I hope this work helps move the conversation toward smarter, more compassionate solutions that allow people to age safely at home and support caregivers in sustainable ways.

Anaraky: As the population ages, more families are navigating dementia with limited resources and fragmented support. At the same time, AI and digital technologies are becoming deeply embedded in everyday life.

This research is important now because it helps ensure that these technologies evolve in ways that are responsive to the complexities of dementia and the lived realities of individuals living with dementia and their caregivers. Rather than retrofitting systems after harm occurs, Assistive Intelligence offers a way to proactively design technologies that support aging populations in humane, adaptive, and ethical ways.

What made you want to work in this area? Do you have a personal connection to the subject of dementia that may have swayed your research journey?

Mohapatra: This work is deeply personal for me, shaped in part by a close family experience

with dementia. Witnessing how the condition unfolds over time has made it clear that

dementia affects not only the person, but the entire family- reshaping daily life,

relationships, and caregiving roles. That perspective strongly informs my commitment

to developing approaches that support both individuals living with dementia and those

who care for them.

I don’t see technology as a replacement for human care, but as a way to support relationships

and to reduce stress, improve communication, and protect dignity.

Anaraky: My motivation is professional, but it is deeply personal in its execution. In my research, I work closely with older adults to understand their lived experiences and the daily friction they encounter with technology. I repeatedly see a gap where digital tools fail, not because the user is “incapable,” but because the tools weren't designed with a proper understanding of the older adult user context.

Working in this area allows me to bring together my interests in Human-Computer Interaction and aging. My goal is to use what I learn directly from the community to design Assistive Intelligence that respects the user’s dignity. I want to ensure that as technology advances, it serves the aging population rather than marginalizes them.

Next Step

Discover stories showcasing LSU’s academic excellence, innovation, culture, and impact across Louisiana.